SPOTLIGHT FEATURE // AFRICAN VISUAL STORYTELLER

THE MODERN MUSE SERIES

REDEAT WONDEMU – REFRAMING THE EVERYDAY WOMAN

Feature by Aida Glowik

Published February 28, 2022

Instagram: @africanvisualstoryteller

ARTIST BIO

Redeat is an Eritrean-born, Ethiopian-American bred photographer based in Washington D.C.

Website: www.simplyred8.com

Instagram: @itslikered8

Spotlight Feature | The Modern Muse Series

Redeat is an analog photographer who takes portraits using a medium format film camera.

Tools: Hasselblad 501c and Kodak 400 Tmax film

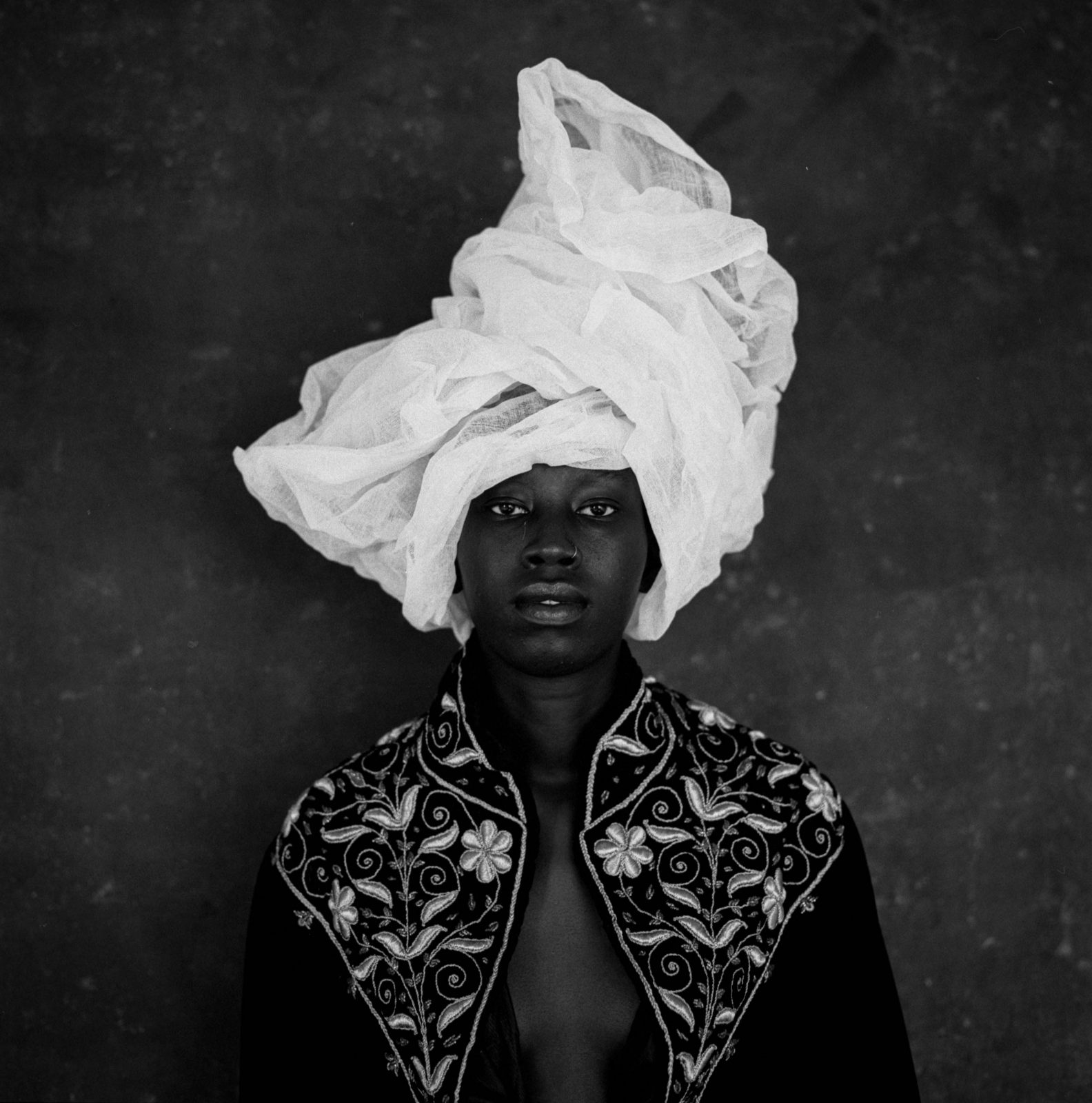

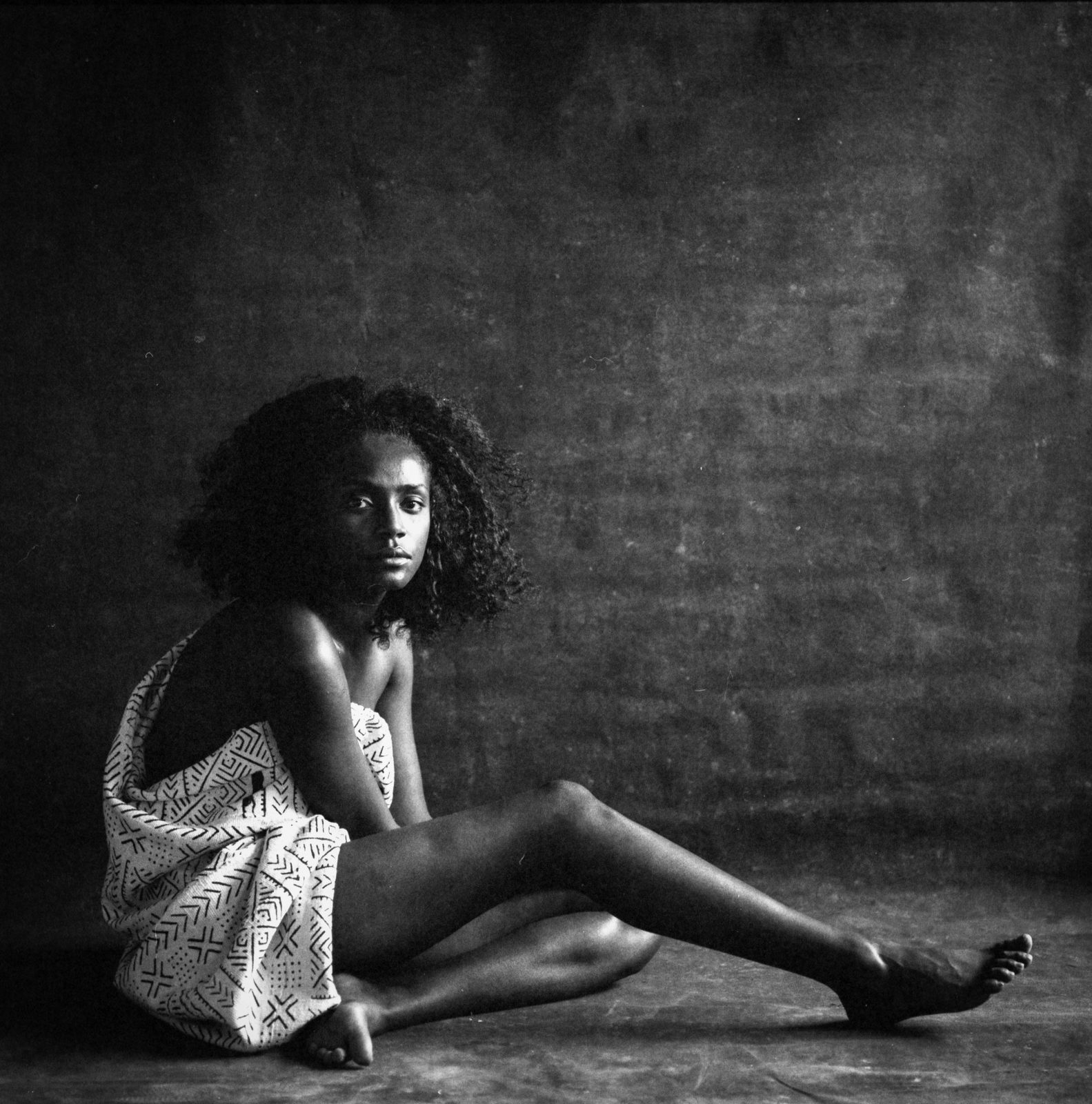

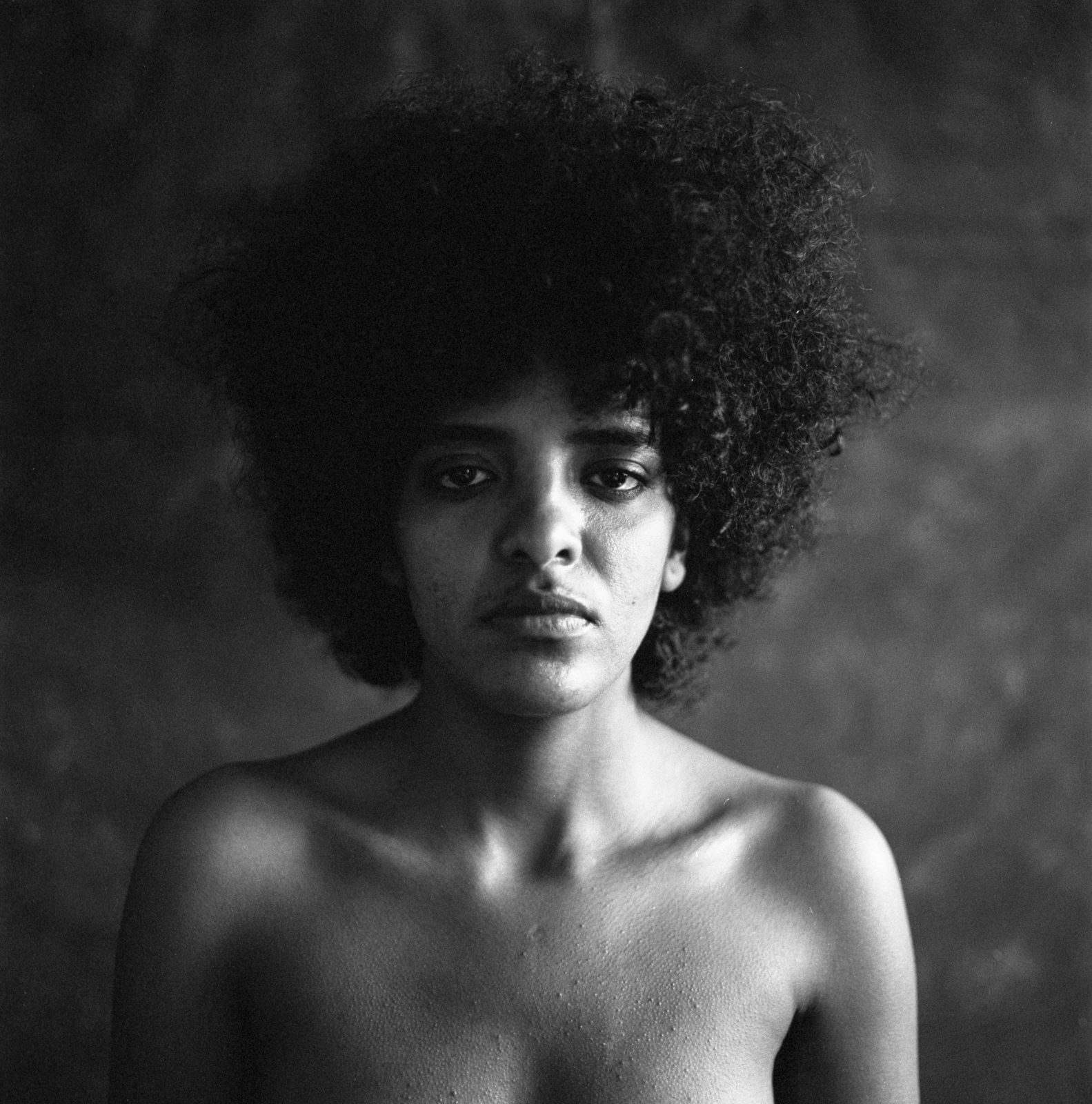

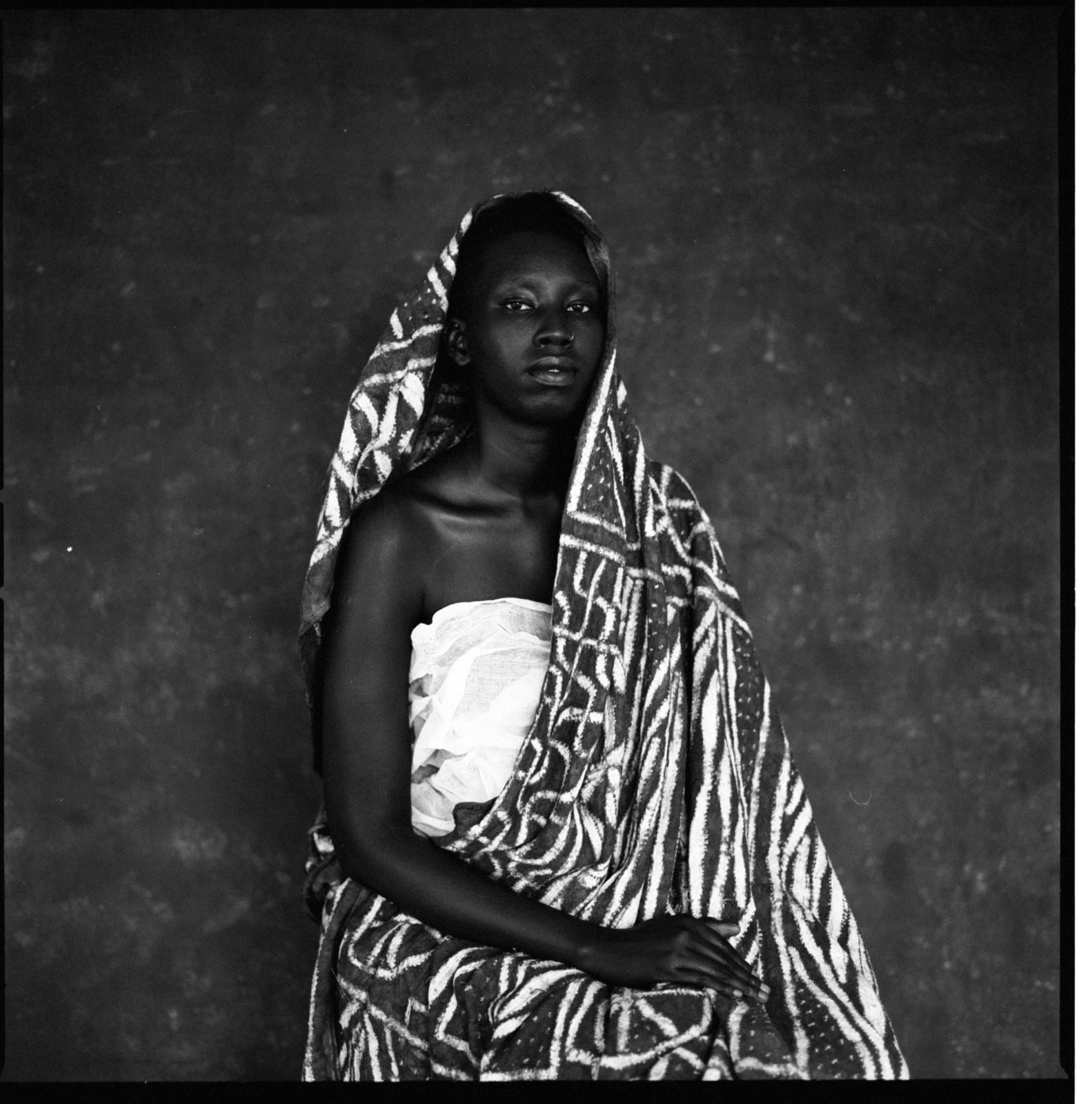

The Modern Muse Series is a collection of black and white portraits of Ethiopian women.

Thank you Redeat for participating in this interview.

1. On your website, you describe the intention behind creating the Modern Muse Series as being a means to explore an unconventional standard of beauty. Can you expand a bit further on this notion?

What I meant by exploring unconventional standards of beauty is wanting to photograph the Muse in a different way. I wanted to photograph women just the way they are, aka without makeup and without having to use photoshop. This desire came when I first moved to Addis Ababa in 2019 and I saw a lot of photographers were taking photos of women with a lot of makeup on and their photos were always photoshopped to perfection. This made me want to explore deeper how women in general are viewed and depicted. To get closer to the truth I began to look at classical painters and photographers. The type of women they depicted as a muse were fair skinned, helpless, and oftentimes looked like a damsel in distress. I wanted to get away from the cliché and find my own definition of beauty by deconstructing the Muse. So when I say I’m looking for an unconventional standard of beauty I mean to say it in terms of underrepresented beauty which to me is natural beauty.

2. In the past, how do you feel women have been portrayed in photography and other forms of art?

What sort of impact has it made?

Women have usually been depicted from the male artist or photographers perspectives, especially in Addis Ababa. When women are viewing themselves from a male perception it has a tremendous impact on their psyche. For example in my photos I tend to show women’s skin and it’s done in a tasteful way because it’s a collaboration between my sitter and I. I want to remove this notion of patriarchy tradition and challenge it by the way I show women’s bodies. So we have so much to do in terms of confronting kitschy images of women and instead showing the natural beauty of women in Ethiopia.

3. What sort of power do you feel photographs (and by extension photographers) possess in setting a standard of beauty in society?

I believe images are powerful and they have the ability to tell a story. When we take photos of people we have a huge responsibility. That responsibility is to tell the truth. And unfortunately some photographers distort the truth in their images. The impact this has made on young women and even me is significant. We learn to believe highly edited images are the truth, when they are far from it. So photography and photographers have a powerful tool and it’s our responsibility to use this tool carefully.

4. How important do you feel it is to have an African woman behind the lens capturing African women?

Can you speak to the difference that it makes?

I can share with you from my experience photographing Ethiopian women. I had a commissioned work that came through. She had a major life event happen and she had finally come up with the decision to get her portraits done with a film camera. She reached out to me after we had our first meeting where we got to know each other and we set up the date for the portrait session. When that day came and I was taking her photos, she seemed to feel more relaxed because I made her feel like she can be herself and say what she needed and if we had to stop because she needed space to explore some emotions that were coming up, I had time and ears for that. Needless to say the photo session went really well. She thanked me for creating a space for her to process her emotions, that I didn’t force her to take smiling pictures and that I valued her body the way it was. This meant a lot to me. Moments like this affirms that my work as an Ethiopian portrait photographer is important. I’m not saying other photographers can’t take beautiful photos. I’m just saying having that commonality and connection opens the door for genuine emotion to appear. And when you capture an image of someone and they are looking real, genuine, simply themselves we all know as photographers those make great portraits.

5. You have been able to share and exhibit the Modern Muse Series. What kind of feelings were you hoping the images would invoke? What kind of response did you receive and what sort of impact has it had thus far?

It took me a long time to share my art with the world. When I decided to share it and I had my first show I really just wanted people to come and connect with the images. And many people who came and saw my work had all kinds of feelings. I’ve had instances where someone who was overcome by emotions towards the images started to cry in front of me after seeing my work. Sharing my art has allowed me to meet strangers from different walks of life to open up and talk to me about their desires, dreams, plans, and love for photography and art after seeing my photos. And I’ve come to welcome and appreciate all feelings with an open heart. Art is a powerful unifier. It can make people come together and evoke authentic feelings from the depth of our souls.

6. Through the making of this series, you have been able to have heartfelt conversations with several women and connect with them on a deeper level.

What was that like for you and what did you learn?

It was a very special feeling and I felt honored to know the women I photographed. Prior to our initial meeting at my studio in Addis, I didn’t know my sitters. I met them by approaching them because they had the look I wanted for my series. So when they come to my studio after I approached them it’s because they trusted me. When they came I would ask each one of them how their trip was to my studio. They all had similar answers about how it took a few taxis or buses to get to me and in some instances they came from far away. I was so grateful for this gesture because they didn’t have to do it, but they believed in my project and they shared their lives with me. I have a huge responsibility to share it with the world the best way I can. One of the things I do is to bring a print that I made in the dark room and give it to them. The idea with the series is ongoing. I’ll plan to photograph them for the next few years so having a deep connection matters to me.

7. What was the thought process behind the visuals: selecting the garment/props and producing the images in black and white?

I obviously enjoy shooting film photography. It’s very nostalgic and dreamy and reminds me of growing up in Addis watching my dad take family pictures. I wanted to create a feeling like the photos were taken a long time ago, but I wanted to incorporate modern elements like showing some skin and artifacts that were common to Ethiopians. So that’s why I choose this medium. I also meet with my sitter prior to the photo shoot and get to know them and ask them to take a feminine archetype assessment. I pre-conceptualize my entire look so I start by sketching and painting my own backdrop. To me all of this work is an expression of my art and who the women are. I don’t try to make them be someone else, but I use what I’ve gathered from them and use props and garments that can best describe their specific feminine archetype and take photos of them.

8. Can you speak to the technical aspect of your work?

What type of camera do you use and what does the post-processing workflow entail?

I use a Hasselblad 501c medium format camera. When I moved to Addis I looked for a darkroom for about a year and found out that they had all closed. So I needed to go to Germany or DC to process my film. So the journey is super cumbersome. I get into a lot of arguments at the airport checkpoint because they want to run my films through the X-ray. When I finally bring it back to the darkroom, I develop my own film and make my own prints. This entire process takes months from shooting to developing and about 10 hours total from developing to printing and toning the silver gelatin prints to make them archival.

9. Looking ahead into the near future, what would you like to see more of when it comes to portraits of women?

I’d love to see portraits that celebrate all types of women’s bodies. Without makeup and photoshop.

Photographs in this spotlight feature by: Redeat Wondemu

Exhibitions

- Solo show 2021: Homme Gallery, Washington D.C. Titled: Modern Muse Series

(selenium toned for archival Silver gelatin prints)

- Solo show 2021: Addis Ababa Museum, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Titled: Modern Muse Series

(archival pigment prints) - Solo exhibition 2020: Washington D.C. Modern Muse Series curated at an outside venue. Titled: Muse in a Garden.